Context:

The Union Tribal Affairs Ministry will be looking into the forest clearance paperwork of the ₹72,000-crore infrastructure project on Great Nicobar Island. It brings the contentious and difficult choices that governments face while addressing the trilemma of infrastructure development, preserving pristine biodiversity respect and, being sensitive to the rights of the indigenous inhabitants, and tribals.

Where is Great Nicobar and Which are the Communities Living There?

The island of Great Nicobar is the southernmost tip of India and a part of the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago that comprises 600-odd islands. It is hilly and covered with lush rainforests that are sustained by around 3,500 mm of annual rainfall. The rainforests and beaches host numerous endangered and endemic species, including the giant leatherback turtle, the Nicobar megapode, the Great Nicobar crake, the Nicobar crab-eating macaque, and the Nicobar tree shrew. It has an area of 910 sq km with mangroves and Pandan forests along its coast.

- Tribal Communities

- The island is home to two tribal communities — the Shompen and the Nicobarese. The Shompen, around 250 in total, mostly live in the interior forests and are relatively isolated from the rest of the population. They are predominantly hunter-gatherers and are classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group within the list of Scheduled Tribes.

- The Nicobarese community practices farming and fishing. It has two groups: the Great Nicobarese and the Little Nicobarese. They use different dialects of the Nicobarese language (the Shompen have their own unique language). The Great Nicobarese lived along the island’s southeast and west coast until the tsunami in 2004, after which the government resettled them in Campbell Bay. Today, there are around 450 Great Nicobarese on the island. Little Nicobarese, numbering around 850, mostly live in Afra Bay in Great Nicobar and also in two other islands in the archipelago, Pulomilo and Little Nicobar.

- The island is home to two tribal communities — the Shompen and the Nicobarese. The Shompen, around 250 in total, mostly live in the interior forests and are relatively isolated from the rest of the population. They are predominantly hunter-gatherers and are classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group within the list of Scheduled Tribes.

- Settlers

- The majority of the population on Great Nicobar comprises settlers from mainland India. Between 1968 and 1975, the Indian government settled retired military servicemen and their families from various states, including Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

- Around 330 households were allotted approximately 15 acres of land each across seven revenue villages on the island's east coast: Campbell Bay, Govindnagar, Jogindernagar, Vijaynagar, Laxminagar, Gandhinagar, and Shastrinagar. Campbell Bay serves as the administrative hub with local offices and the panchayat.

- Additionally, there have been migrations of fisherfolk, agricultural and construction laborers, businesspersons, and administrative staff from the mainland and the Andaman Islands. After the 2004 tsunami, construction contractors also arrived. The current population of settlers on the island is around 6,000, based on estimates from researchers.

- The majority of the population on Great Nicobar comprises settlers from mainland India. Between 1968 and 1975, the Indian government settled retired military servicemen and their families from various states, including Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

What is the NITI Aayog Project?

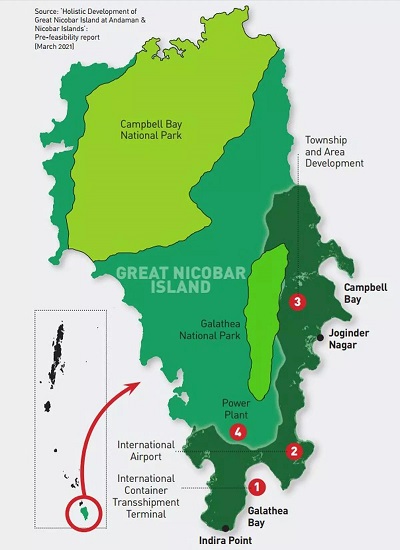

In March 2021, NITI Aayog unveiled a ₹72,000 crore plan called ‘Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island at Andaman and Nicobar Islands.’ It includes the construction of an international transshipment terminal, an international airport, a power plant, and a township. The project is to be implemented by a government undertaking called the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation (ANIIDCO).

Project Objectives

- The plan states: “The proposed port will allow Great Nicobar to participate in the regional and global maritime economy by becoming a major player in cargo transshipment. The proposed airport will support the growth of maritime services and enable Great Nicobar Island to attract international and national visitors to experience the outstanding natural environment and participate in sustainable tourism activity.” Although NITI Aayog put forth the project in its present form, it has a long history.

- Plans for developing a port in Great Nicobar have been around since at least the 1970s, when the Trade Development Authority of India (now called ‘India Trade Promotion Organization’) conducted techno-economic feasibility studies. The core aim has persisted since then — a port located near one of the world’s busiest international sea routes (the Malacca Strait) which will allow increased participation in global maritime trade.

Why is There Opposition?

- Ecological Costs

- The mega project has been heavily criticized for its ecological costs and for potential violations of tribal rights. The project requires the diversion of about 130 sq km of forest land and the felling of around 10 lakh trees. In January 2021, the Indian government denotified two wildlife sanctuaries — the Galathea Bay wildlife sanctuary and the Megapode wildlife sanctuary — to make way for the project. In the same month, the government released a ‘National Marine Turtle Action Plan’ that lists Galathea Bay as a marine turtle habitat in India.

- The transshipment terminal is expected to be developed at Galathea Bay, one of the world’s largest nesting sites for the giant leatherback turtle. Both this species and the Nicobar megapode are listed in Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection Act), 1972 — the highest level of protection for wild animals under Indian law (numerous species, especially endemic ones, are likely yet to be documented in Great Nicobar given the limited number of surveys conducted so far).

- The mega project has been heavily criticized for its ecological costs and for potential violations of tribal rights. The project requires the diversion of about 130 sq km of forest land and the felling of around 10 lakh trees. In January 2021, the Indian government denotified two wildlife sanctuaries — the Galathea Bay wildlife sanctuary and the Megapode wildlife sanctuary — to make way for the project. In the same month, the government released a ‘National Marine Turtle Action Plan’ that lists Galathea Bay as a marine turtle habitat in India.

- Tribal Rights and Consent

- The Tribal Council of Great Nicobar and Little Nicobar withdrew their no-objection certificate (NOC) for the project, citing the administration's concealment of key information about tribal reserve lands and a rushed consent process.

- Some land classified as "uninhabited" in NITI Aayog’s plan is actually part of the Great Nicobarese’s ancestral land. Since their resettlement after the tsunami, they have repeatedly sought to return to these lands but faced administrative apathy. The mega project now obstructs their efforts to reclaim their ancestral land.

- The Tribal Council of Great Nicobar and Little Nicobar withdrew their no-objection certificate (NOC) for the project, citing the administration's concealment of key information about tribal reserve lands and a rushed consent process.

- Health Risks for Shompen

- As for the Shompen, one of the biggest threats is disease. Since the Shompen have had little contact with the outside world, they haven’t yet developed immunity to infectious diseases that affect India’s general population. Some Shompen settlements also overlap with the areas the NITI Aayog has proposed to be used for the transshipment terminal.

- As for the Shompen, one of the biggest threats is disease. Since the Shompen have had little contact with the outside world, they haven’t yet developed immunity to infectious diseases that affect India’s general population. Some Shompen settlements also overlap with the areas the NITI Aayog has proposed to be used for the transshipment terminal.

- Social and Environmental Concerns

- The local panchayat of Campbell Bay raised concerns over the social impact assessment process for land acquisition for the airport. Researchers who work on disaster management have also raised concerns that proponents of the mega project have failed to adequately assess earthquake risk.

- The Andaman and Nicobar archipelago is located in the “ring of fire”: a seismically active region that experiences several earthquakes throughout the year. According to some estimates, the region has experienced close to 500 quakes of varying magnitude in the last decade. The area is in category V: the geographical zone with the most seismic hazard.

- The local panchayat of Campbell Bay raised concerns over the social impact assessment process for land acquisition for the airport. Researchers who work on disaster management have also raised concerns that proponents of the mega project have failed to adequately assess earthquake risk.

Conclusion

The NITI Aayog project on Great Nicobar Island presents a complex challenge. Balancing economic development with environmental and social considerations requires careful planning. A thorough environmental impact assessment and transparent consultations with all stakeholders, including tribal communities, are crucial. Sustainable development must prioritize protecting the island's unique ecology and respecting the rights and traditions of its indigenous inhabitants. Finding alternative locations or scaling down the project's footprint could be explored to minimize ecological damage. Ensuring the safety of the Shompen from diseases and the island's resilience to natural hazards like earthquakes needs meticulous consideration. Only through an inclusive and sustainable approach can the future of Great Nicobar be secured.

|

Probable Questions for UPSC Mains Exam-

|

Source- The Hindu