Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), often known as Naxalism, has remained one of India’s most pressing internal security concerns for over five decades. While the movement initially emerged from ideological motivations such as class struggle and agrarian issues, its present form is influenced by a mix of socio-economic underdevelopment, weak governance, and ongoing violence. A significant portion of this activity is concentrated in the “Red Corridor”—a stretch of districts affected by Naxal violence across central and eastern India.

Understanding the Origins and Ideology

- The Naxalite movement originated in 1967 in the village of Naxalbari in West Bengal, when a section of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) launched an armed uprising demanding land redistribution and justice for marginalized peasants. The movement drew ideological inspiration from Mao Zedong’s principles of protracted people’s war, advocating the overthrow of the state through armed struggle.

- Over the decades, LWE splintered into multiple factions. However, in 2004, the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) People’s War Group and the Maoist Communist Centre of India merged to form the CPI (Maoist), which today leads the insurgency. The group’s stated objective is to wage a “people’s war” against the “bourgeois Indian state” and establish a Maoist regime.

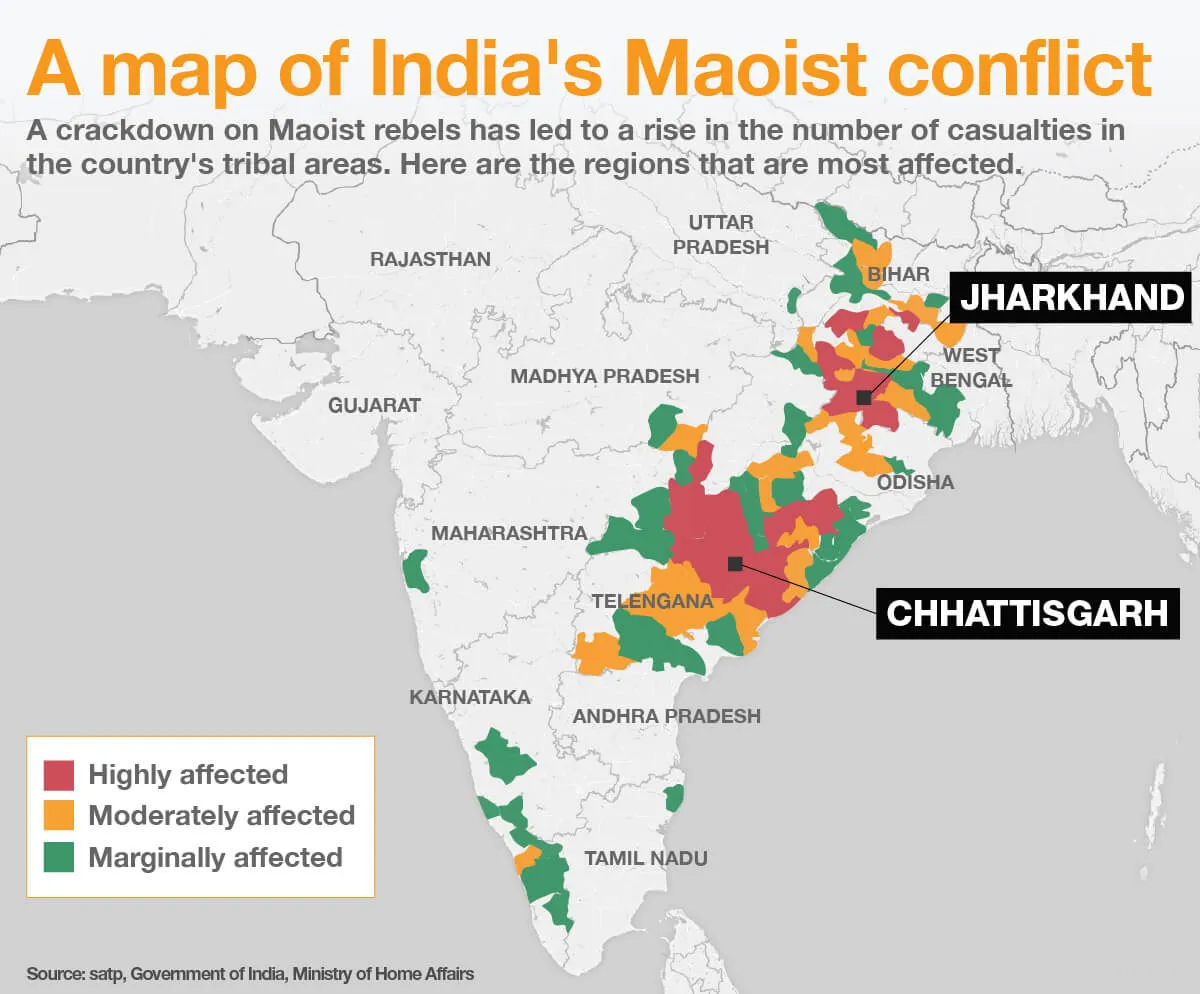

About the Red Corridor:

The term Red Corridor refers to the region in India significantly affected by LWE. At its peak, this corridor is stretched across more than 200 districts in 20 states. Over time, through coordinated state and central interventions, the spread has narrowed. As of 2023, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has identified 70 districts in 10 states as LWE-affected, with 25 districts listed as “most affected”.

Key States in the Red Corridor Include:

- Chhattisgarh: Especially the Bastar region, which has witnessed some of the most intense Maoist violence. Dense forests and difficult terrain make it a stronghold.

- Jharkhand: A mineral-rich state with significant tribal populations facing displacement and land alienation.

- Odisha: Southern districts such as Malkangiri and Koraput have seen periodic violent activities and recruitment.

- Bihar and Maharashtra: Areas along inter-state borders are especially vulnerable.

- Andhra Pradesh and Telangana: Earlier hotbeds of Maoist activity, now largely under control due to sustained counter-insurgency efforts.

Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Red Corridor:

- High Tribal Population: Many districts in the Red Corridor have a significant Scheduled Tribe (ST) population, whose traditional land rights have been historically ignored or overridden.

- Underdevelopment: These areas lag behind national averages in health, education, road connectivity, digital access, and basic infrastructure.

- Alienation and Exploitation: Displacement due to mining, industrial projects, and lack of forest rights have led to a sense of disenfranchisement.

- Weak Governance: Inaccessibility, administrative apathy, and poor delivery of welfare services have eroded the credibility of state institutions.

These conditions have created a vacuum where Maoists have, at times, projected themselves as an alternative authority by resolving disputes, running informal courts (jan adalats), and collecting taxes (levy).

Government Response:

1. Security Interventions

- Deployment of Central Armed Police Forces (CAPFs): Specialized forces such as CRPF’s CoBRA units have been deployed in core affected areas.

- Establishment of fortified police stations: Focus on strengthening security infrastructure in remote areas.

- Unified Command Structure: Joint coordination among centre, state police, and intelligence agencies has improved operational efficiency.

2. Developmental Approach

- Road Connectivity Projects: Under schemes like the Road Requirement Plan-I and II, roads are being constructed in forested and remote tribal regions.

- Skill Development and Livelihood Support: Programs such as ROSHNI, DDU-GKY, and National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) aim to provide income opportunities for tribal youth.

- Mobile and Digital Connectivity: Expansion of telecom infrastructure in dense forests is helping bridge the information gap.

- Education and Health Infrastructure: Construction of residential schools (Eklavya Model Residential Schools) and mobile medical units.

3. Surrender and Rehabilitation Policies

- The MHA supports state governments in implementing attractive surrender and rehabilitation policies offering financial assistance, vocational training, housing support, and education for children.

- These schemes aim to encourage cadre-level Maoists to return to the mainstream.

4. SAMADHAN Strategy

Launched by the Ministry of Home Affairs, SAMADHAN is an umbrella policy that includes:

- Smart leadership

- Aggressive strategy

- Motivation and training

- Actionable intelligence

- Dashboard-based Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

- Harnessing technology

- And

- No access to financing or arms for Maoists

Trends and Progress

India has witnessed a steady decline in LWE-related violence:

- According to MHA data, incidents of violence have reduced by over 77%, and deaths by more than 90% between 2010 and 2023.

- States like Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have seen a near elimination of Maoist presence.

- The number of LWE-affected districts has also declined substantially due to effective implementation of the security-development strategy.

Remaining Challenges in the Red Corridor

- Geographic Cover and Terrain: The dense forests of Bastar, Abujhmad, and parts of Odisha offer tactical advantages to Maoists and hinder security operations.

- Local Grievances and State Absence: In many areas, people still perceive state institutions as corrupt or unresponsive, while Maoist networks are seen as more approachable.

- Recruitment and Radicalization: Disillusioned tribal youth with limited education and opportunities remain vulnerable to Maoist recruitment drives.

- Inter-State Coordination Gaps: Naxal groups often exploit administrative boundaries and jurisdictional limitations.

The Way Forward

- Strengthen grassroots governance: Implementation of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA) and Forest Rights Act (FRA) must be prioritized to empower tribal communities.

- Improve last-mile delivery: Welfare schemes should reach the most remote villages without leakages or delays.

- Build trust through civil society: NGOs, local leaders, and social workers can help build bridges between the state and citizens.

- Invest in education and opportunity: Schools, digital learning, and skill centres should be accessible to every tribal hamlet.

- Continue the dual strategy: Maintain pressure on armed cadres while expanding the state’s developmental footprint.

Conclusion

The Red Corridor, once synonymous with insurgency and violence, is now undergoing a transformation. However, the deep structural issues—land alienation, tribal marginalization, and developmental exclusion—require sustained attention. The decline in Left-Wing Extremism should not lead to complacency. Only by combining robust security with genuine socio-economic empowerment can India ensure peace and progress in the Red Corridor.

| Main question: Discuss the role of socio-economic factors in the persistence of Left-Wing Extremism in the Red Corridor. |