In the landmark case of Rajive Raturi v. Union of India (2024), the Supreme Court of India made a transformative ruling regarding accessibility standards for persons with disabilities (PwDs) in the country. The Court declared that Rule 15 of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Rules, 2017, was in violation of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (RPwD Act). The judgment emphasized the need for uniform, mandatory accessibility standards across sectors, urging the government to implement minimum accessibility guidelines in all public and private sectors.

Current Status of Persons with Disabilities in India

According to the Census 2011, India is home to approximately 2.68 crore persons with disabilities, making up 2.21% of the total population. These individuals experience a wide range of disabilities, categorized into 21 types under the RPwD Act, 2016, including Locomotor Disability, Visual Impairment, Hearing Impairment, Speech and Language Disability, Intellectual Disability, Multiple Disabilities, Cerebral Palsy, and Dwarfism.

Despite representing a substantial portion of the population, PwDs in India continue to face significant social, infrastructural, and attitudinal barriers. These challenges prevent many from fully participating in societal, economic, and political life. The need for comprehensive legislative and practical measures to address these barriers has never been more urgent.

Models of Disability Rights

Disability rights have evolved through various models that shape how society supports PwDs. These models emphasize different aspects of disability and the role of society in creating an inclusive environment.

· Medical Model: The medical model of disability views impairment as an individual issue that needs to be addressed through medical intervention and rehabilitation. In this model, the responsibility lies primarily with the individual to overcome the challenges posed by their impairment.

· Social Model: The social model shifts the focus from the individual to society. It posits that disability arises from societal barriers, such as inaccessible infrastructure and discriminatory attitudes, that prevent PwDs from participating fully in society. This model advocates for removing these barriers to promote inclusivity.

· Human Rights Model: An evolution of the social model, the human rights model emphasizes that PwDs should have equal rights and opportunities as all other individuals. This model stresses that disability rights are fundamental human rights, and that PwDs must be fully included in all aspects of life. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Rajive Raturi aligns with this model by obligating both government and private entities to facilitate the full and effective participation of PwDs.

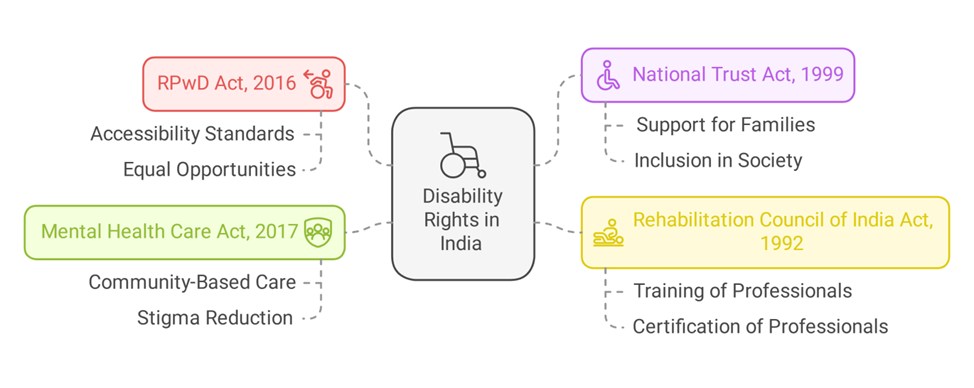

Laws Granting Disability Rights in India

· RPwD Act, 2016: The RPwD Act, 2016, which replaced the 1995 Act, is the cornerstone of disability rights in India. Enacted to ensure equal opportunities and full participation for PwDs, the Act mandates that public and private institutions comply with accessibility standards, providing PwDs with access to education, employment, healthcare, and public services.

· National Trust Act, 1999: The National Trust Act, 1999, focuses on the welfare of persons with autism, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and multiple disabilities. It establishes a national body that provides support and resources to families and caregivers of PwDs, promoting their inclusion in society.

· Rehabilitation Council of India Act, 1992: This Act regulates the training and certification of professionals working in disability rehabilitation. It ensures that qualified personnel are available to support PwDs in areas like education, employment, and healthcare, enabling them to live more independent and fulfilling lives.

· Mental Health Care Act, 2017: The Mental Health Care Act, 2017, protects the rights and dignity of persons with mental illness. It promotes community-based care, aiming to eliminate stigma and ensuring that individuals with mental illness receive care in the least restrictive environment.

The Supreme Court’s Framework and Its Implications

The Supreme Court's ruling in Rajive Raturi marks a critical juncture in India's disability rights journey. The Court’s judgment stressed the need for mandatory, uniform accessibility standards across sectors, both public and private, to ensure that PwDs have equal access to opportunities and services. By striking down Rule 15 of the RPwD Rules, 2017, which allowed departments to create accessibility guidelines at their discretion, the Court reinforced the principle that accessibility must be a fundamental right, not a privilege.

Key Takeaways from the Judgment:

1. Mandatory Accessibility Standards: The ruling calls for legally binding accessibility standards that apply across all sectors, ensuring uniformity and eliminating ambiguity in accessibility implementation. This move aims to reduce regional and sectoral disparities in accessibility.

2. Deadline for Implementation: The Court directed the government to devise a new set of mandatory accessibility guidelines within three months, ensuring that accessibility measures are implemented promptly and effectively.

3. Holistic View of Accessibility: The ruling recognizes the evolving nature of accessibility, expanding its definition to include both physical and digital access. This ensures that PwDs are not excluded from technological advancements and can fully participate in a digital society.

The Evolution of Accessibility

Accessibility is no longer confined to physical infrastructure but has evolved into a comprehensive concept that addresses various barriers—both physical and digital. The growing dependence on technology and the need for inclusivity in the digital space has shifted the focus to digital accessibility.

- Physical Accessibility: Traditionally, accessibility referred to the removal of physical barriers in the environment, such as ramps, elevators, and wider doorways.

- Digital Accessibility: With the advent of the digital age, there is an increasing demand for accessible digital platforms, such as websites and mobile applications. The integration of AI and IoT into everyday life means that accessibility standards must now extend to digital environments, ensuring that PwDs can access information, services, and technology with ease.

The Way Forward:

· Simplification of Guidelines: Existing accessibility guidelines are often complex and difficult to navigate. Simplifying and standardizing these guidelines will make it easier for public and private institutions to comply with accessibility standards.

· Centralized Authority for Oversight: A centralized authority, potentially under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, should be established to oversee the implementation of accessibility standards. This body would be responsible for ensuring consistency and providing guidance on best practices.

· Involvement of the Private Sector: Both public and private sectors must play an active role in ensuring accessibility. While the government is responsible for setting legislative frameworks, private sector entities should be incentivized to make their products and services accessible to PwDs.

· Education and Awareness: To foster inclusivity, there must be a societal shift in attitudes toward disability. Public education and awareness campaigns can help eliminate stigma and encourage greater acceptance of PwDs as equal members of society.

· Technology and Innovation: The rapid advancement of technology must be leveraged to enhance accessibility. This includes ensuring that digital platforms, public services, and everyday tools are accessible to all, including PwDs.

| Main question: Analyze the current status of persons with disabilities (PwDs) in India, highlighting the barriers they face in accessing education, employment, and public services. What role do legislative measures play in addressing these challenges? |