Context:

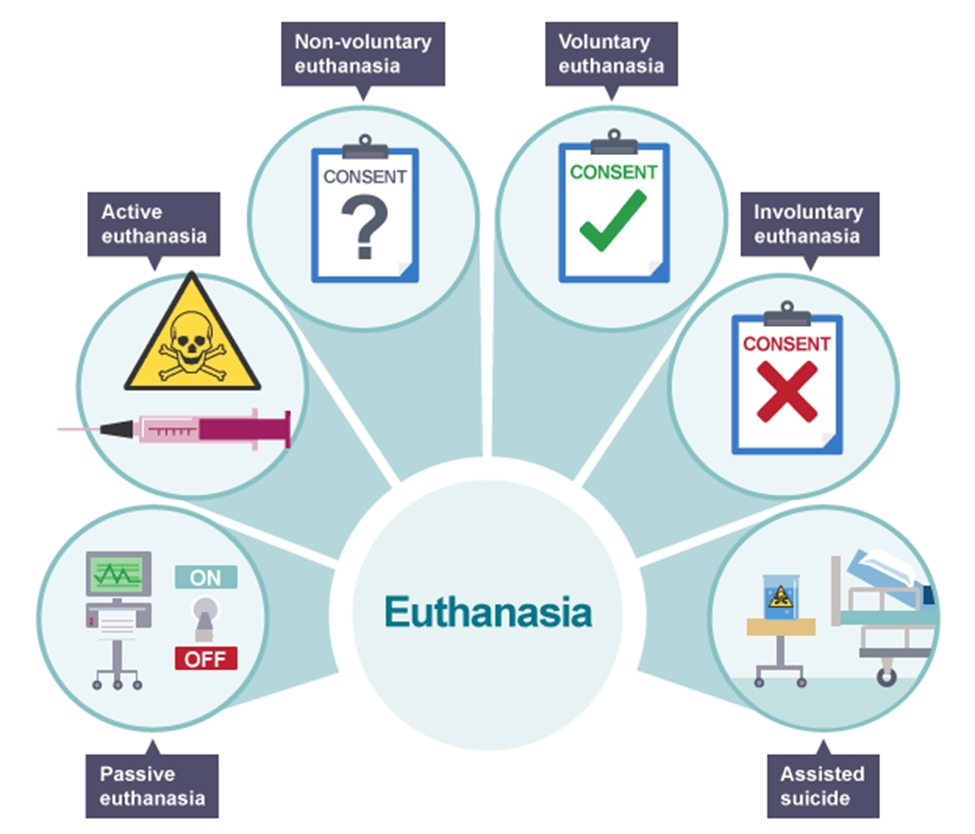

Passive euthanasia, the practice of withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment from terminally ill patients, has been an evolving and contentious topic in India. Recently, the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) introduced new draft guidelines aimed at streamlining this process, responding to legal, ethical, and practical concerns within India’s healthcare landscape.

Legal Evolution of Passive Euthanasia in India:

- In India, the Supreme Court recognized the right to die with dignity in the 2018 Common Cause v. Union of India ruling, establishing a legal framework for passive euthanasia under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. This judgment permitted Advance Medical Directives (AMDs), allowing patients to document their preferences for end-of-life care, including instructions for life support withdrawal. However, the 2018 guidelines mandated multiple layers of judicial and medical review, which stakeholders, including the Indian Society for Critical Care Medicine, viewed as burdensome.

- To address these challenges, the DGHS recently proposed new draft guidelines to simplify the passive euthanasia process, emphasizing compassion, respect for patient autonomy, and ethical responsibility. The updated guidelines reflect the government’s commitment to making end-of-life decisions more accessible, legally sound, and patient-centered.

Key Provisions of the DGHS Guidelines:

The new DGHS guidelines outline criteria and procedures to facilitate passive euthanasia while protecting patient rights and ensuring legal compliance. Key provisions include:

1. Conditions for Withdrawal of Life Support: Passive euthanasia may be considered when:

o A patient is declared brainstem dead under the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA).

o Medical assessments indicate no benefit from continued treatment, such as in advanced, incurable diseases.

o A documented refusal from the patient or their legal surrogate expresses a wish to forgo life-sustaining treatment.

o All procedures adhere to Supreme Court protocols, ensuring legal and ethical soundness.

2. Streamlined Medical Board Requirements: The 2018 guidelines required a two-stage review by medical boards, each with doctors having at least 20 years of experience. The DGHS now allows doctors with a minimum of five years of experience, reducing the board to three members, making it easier for hospitals, especially in smaller facilities, to comply with the guidelines.

3. Time Limits for Decision-Making: To minimize prolonged suffering, the DGHS introduces a 48-hour window for both the primary and secondary medical boards to render decisions. This provision aims to expedite care for terminally ill patients, ensuring timely and compassionate decision-making.

4. Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation (DNAR) Orders: For the first time, DNAR orders are addressed, allowing doctors to refrain from resuscitation efforts (CPR) when survival prospects are negligible. This addition highlights the importance of respecting the patient’s right to a dignified death by avoiding unnecessary medical interventions.

5. Legal and Ethical Safeguards: The guidelines affirm patient autonomy, allowing those with decision-making capacity to decline life-sustaining treatment. In cases where patients are incapacitated, a primary medical board (PMB) consensus, validated by a secondary board (SMB), is required. This layered approach offers ethical oversight and legal accountability.

Potential Benefits of the DGHS Guidelines:

1. Enhancing Patient Autonomy: By allowing patients to articulate end-of-life preferences through AMDs, the guidelines promote individual rights and respect for personal dignity. This reassures patients that their values and choices will be honored, contributing to a more humane healthcare system.

2. Reducing Financial and Emotional Burden on Families: For many families, life-sustaining treatments represent a significant financial and emotional strain. By enabling withdrawal of treatment when recovery is not possible, the guidelines alleviate this burden, allowing families to focus on supportive care and personal time with their loved ones.

3. Easing Healthcare Infrastructure Pressure: Passive euthanasia helps optimize healthcare resources by reallocating critical care beds and equipment to patients with treatable conditions. This efficient resource use has a ripple effect, potentially enhancing the overall quality and availability of healthcare in India.

4. Providing Clarity for Medical Practitioners: A structured framework for end-of-life care decisions helps healthcare providers navigate these sensitive decisions without legal ambiguity. Clear protocols reduce hesitation among practitioners, empowering them to provide compassionate care within a legally protected framework.

Challenges and Criticisms:

1. Risk of Misuse and Legal Challenges: The Indian Medical Association (IMA) and others express concern about potential litigation if families contest life support withdrawal, indicating a need for additional legal safeguards.

2. Cultural and Religious Sensitivities: India’s diverse religious landscape could present resistance to passive euthanasia, as some communities may view it as morally unacceptable.

3. Informed Consent and Health Literacy: Given variable literacy rates, ensuring that patients and families understand passive euthanasia fully is crucial, especially in rural areas. Public education campaigns are essential.

4. Emotional and Psychological Impact on Families: End-of-life decisions can be distressing, and India’s cultural emphasis on family caregiving heightens this emotional toll. Counseling and palliative care support can help families cope with the difficult decisions.

Global Perspectives on Euthanasia and Assisted Dying:

· Europe: In countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, both active euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are permitted under strict conditions. Patients must demonstrate unbearable suffering and undergo multiple medical evaluations.

· Switzerland: Swiss law allows physician-assisted suicide, including for non-residents, through organizations like Dignitas. This model has attracted international attention, despite ethical debates.

· Canada: In 2016, Canada introduced Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID), with mandatory assessments and a waiting period to ensure informed consent.

· United States: States like Oregon and Washington have “Death with Dignity” laws permitting physician-assisted suicide but prohibiting active euthanasia.

Way Forward:

The DGHS guidelines represent an important step toward compassionate and patient-centered end-of-life care in India. However, effective implementation will require:

· Expanding Palliative Care: Enhanced palliative care services can offer alternatives to passive euthanasia by providing comprehensive pain management and emotional support, improving quality of life for terminally ill patients.

· Clarifying Legal Protections: Establishing additional legal frameworks can reassure healthcare providers that they are protected when acting in accordance with the guidelines, minimizing their legal risks and encouraging adherence.

· Promoting Health Literacy and Public Awareness: Increased public awareness and education campaigns can improve understanding of passive euthanasia and the options available, empowering patients and families to make informed decisions aligned with their values.

Passive euthanasia aligns with the broader shift toward patient-centered healthcare by prioritizing dignity, choice, and compassion at the end of life. As India embraces these guidelines, the challenge will be to balance ethical considerations, cultural values, and legal protections, creating a compassionate, transparent, and sustainable approach to end-of-life care.

|

Probable questions for UPSC Mains exam: · Analyze the legal and ethical challenges involved in implementing passive euthanasia in India, especially in light of the recent DGHS guidelines. How can India address these challenges to promote dignity in end-of-life care? · Examine the role of cultural and religious factors in shaping public perceptions of passive euthanasia in India. What steps can policymakers take to ensure a balanced approach that respects diverse viewpoints? |