Date : 31/08/2023

Relevance – GS Paper 2 - International Relations

Keywords – IWT, PCA, World Bank

Context –

- Amidst the historical complexities that have shaped the relations between India and Pakistan, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), a seminal agreement orchestrated by the World Bank, has once again taken center stage.

- Spanning more than six decades, the IWT seeks to harmonize equitable water allocation while preventing potential harm, underscoring the foundations of cooperative diplomacy and sustainable development.

About Indus Water Treaty –

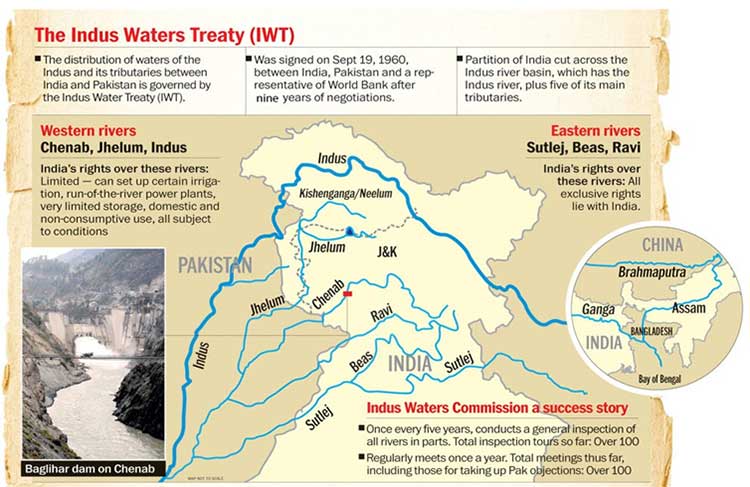

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was signed by India and Pakistan in September 1960 after extensive negotiations, with the participation of the World Bank. This treaty outlines a cooperative framework and information-sharing mechanism for the utilization of the Indus River and its tributaries, namely the Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Jhelum, and Chenab.

Key Provisions:

- Equitable Water Sharing: The IWT delineates the sharing of water from the six rivers of the Indus River System between India and Pakistan. Pakistan was allocated the three western rivers—Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum—for unrestricted use, with limited exceptions for specific non-consumptive, agricultural, and domestic purposes by India. The three eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—were allocated to India for unrestricted usage. This distribution implies that 80% of the water share went to Pakistan, while the remaining 20% was earmarked for India's use.

- Permanent Indus Commission: The treaty mandates the establishment of a Permanent Indus Commission comprising permanent commissioners from both countries. The commission is required to convene at least once annually to facilitate communication and cooperation.

- River Rights: Pakistan has authority over the waters of the Jhelum, Chenab, and Indus rivers. Annexure C of the IWT grants India specific agricultural usage rights, while Annexure D allows India to develop 'run of the river' hydropower projects—projects that do not necessitate significant water storage.

- Dispute Resolution Mechanism: Article IX of the Indus Waters Treaty provides a structured process for dispute resolution. If disputes arise, either side can address them at the Permanent Commission level or escalate them to inter-government discussions. If issues persist, the World Bank can appoint a Neutral Expert (NE) to provide a decision on technical disagreements. In cases of disputes over treaty interpretation and scope, a Court of Arbitration can be invoked when either party is dissatisfied with the NE's decision.

This treaty's provisions encapsulate a carefully balanced framework that addresses water-sharing, river rights, and dispute resolution while acknowledging the specific needs and concerns of both India and Pakistan.

Equitable Allocation: A Cornerstone of Collaboration

- At its heart, the IWT stands as a testament to the principle of equitable allocation, a bedrock principle that encapsulates the essence of equitable sharing of river waters between the two countries.

- Beyond mere water-sharing, the treaty symbolizes a commitment to balanced progress and shared prosperity, signifying a pivotal aspect of diplomatic cooperation.

- This emphasis on fairness seeks to establish a common ground that acknowledges each nation's right to utilize the waters without compromising the other's interests.

Partition and Utilization of Rivers: Navigating Responsibilities

- Integral to the IWT's architecture is the partitioning of rivers into distinct categories, each assigned to the care of one of the nations. India is endowed with unrestricted access to the three eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—while Pakistan similarly enjoys exclusive rights over the three western rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab.

- This allocation empowers India to store up to 3.60 million feet (MAF) of water, dispersed across an array of sectors encompassing conservation, power generation, and flood control. This careful allocation delineates the boundaries of responsibility, ensuring that each nation can harness the waters for its development needs.

Hydropower Projects and Emerging Disputes

- Amidst this intricate backdrop, the focus of current disagreements lies on two pivotal hydropower projects: the Kishanganga and Ratle hydroelectric power plants located within India's Jammu and Kashmir.

- From India's standpoint, these projects are indispensable for satisfying its energy demands and propelling regional growth.

- However, Pakistan voices apprehensions concerning potential breaches of the treaty's provisions and far-reaching implications for its water supply, as stipulated within Annexure D of the IWT.

- This contention highlights the delicate balance between developmental aspirations and the preservation of shared resources.

A Chronicle of Disagreements: Tracing Historical Narratives

- The genesis of the present-day dispute traces back over a decade. In 2006, Pakistan first raised concerns about the Kishanganga project, followed by objections to the Ratle project in 2012.

- Subsequently, the Kishanganga matter was escalated to the Court of Arbitration (CoA) in 2010. In 2013, the CoA's verdict acknowledged India's prerogative to divert water from the Kishanganga River for power generation, albeit with the caveat of maintaining a minimum water flow. This timeline illustrates the complexities of resolving disputes within the framework of an established treaty.

A Stalemate and External Mediation: The World Bank's Role

- Despite repeated rounds of negotiations spearheaded by the Indus Water Commissioners of both nations, significant issues entailing spillway configuration remained unresolved.

- Pakistan sought recourse with the World Bank, alleging that India's actions violated both the IWT and the court's ruling. Responding to the dispute, the World Bank intervened by suspending work on the Kishanganga and Ratle projects, encouraging both countries to explore alternative dispute resolution methods.

- This external intervention signifies the importance of third-party involvement in addressing disputes with international ramifications.

Legal Proceedings and India's Strategic Response

- The year 2016 witnessed Pakistan's plea for the establishment of a Court of Arbitration, countered by India's advocacy for the appointment of a neutral expert. Subsequent legal proceedings underscored the intricate and multifaceted nature of the case.

- In 2023, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) unanimously asserted its jurisdiction over the matter. However, India refrained from participating, arguing against the legitimacy of the proceedings. This strategic approach emphasizes the intricacies of diplomatic maneuvers within the framework of international law.

Charting a Path to Reconciliation: A Redefined IWT

- Amidst the labyrinthine complexity of challenges, proponents advocate for the redefinition of the IWT to incorporate tenets such as "equitable and reasonable utilization" and the "no harm rule."

- Realizing these amendments, however, hinges on the establishment of a conducive diplomatic environment and the restoration of mutual trust, which has waned due to an array of factors.

- This reframing of the treaty reflects the evolving understanding of the nuanced relationship between developmental aspirations and ecological preservation.

Collaborative Strategies: The Journey to Resolution

- To craft a viable route towards resolution, suggestions have arisen to actively integrate local stakeholders and experts into the negotiation processes concerning shared water resources.

- The establishment of a collaborative committee, featuring technical experts, climate scientists, water management professionals, and researchers from both nations, could foster a deeper comprehension of the multifaceted challenges intertwined in the issue.

- This multi-disciplinary approach underscores the need for comprehensive insights to address a multifaceted issue.

Leveraging Untapped Mechanisms: Exploring Article VII and Mutual Goals

- Article VII of the IWT introduces mechanisms for cooperation that have remained largely unexplored. Both India and Pakistan must recognize their shared stake in the comprehensive development of the Indus River System, transcending their existing disputes and nurturing a spirit of harmonious collaboration.

- This dormant provision presents an avenue to facilitate cooperation and reframe the discourse surrounding the management of shared water resources.

Responding to Shifting Realities: The Nexus of Amendments and Trust

- The IWT's conception over six decades ago prompts considerations about its applicability within the evolving context. In response, deliberations about potential amendments have surged.

- However, the modification of any provisions necessitates bilateral consensus and a commitment to trust-building, as unilateral modifications are inherently restricted. This adaptive approach signifies the recognition of changing dynamics and the need for flexible frameworks.

Conclusion

As the intricate narrative woven by the Indus Waters Treaty continues to mold the contours of relations between India and Pakistan, surmounting this intricate terrain demands not only legal acumen but also a resolute dedication to mutual understanding, collaborative efforts, and shared progress. As these neighboring nations strive to transcend the hurdles that lie ahead, they stand at a pivotal juncture in their pursuit of sustainable cooperation in the realm of water resource management. Embracing the challenges and opportunities presented by the evolving context, the two nations have the potential to reshape their relationship on the foundation of shared resources and harmonious development.

Probable Questions for mains exam

- Discuss the Indus Waters Treaty's (IWT) role in fostering cooperation between India and Pakistan. Explain its equitable water allocation principles and potential treaty redefinition to address contemporary challenges. (10 marks, 150 words)

- Examine the hydropower projects dispute under the Indus Waters Treaty. Evaluate international interventions, legal proceedings, and the role of local stakeholders in resolving India-Pakistan water conflicts. (15 marks, 250 words)

Source – The Hindu