Context:

The Economic Survey that preceded this year’s Union Budget presentation makes a suggestion which has implications for inflation control. It is that the price of food be taken out of the inflation target that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is mandated with. In technical jargon, this would amount to targeting ‘core’ instead of ‘headline’ inflation, which is the practice now. To appreciate fully the implication of such a move, were it to be implemented, would require recognition of two aspects. These concern the recent experience with inflation in India and the current policy for inflation control.

Food Price Inflation

Persistent Food Price Inflation

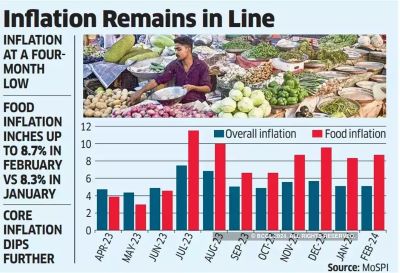

In recent times, food price inflation in India has been unusually high. In June 2024, the year-on-year increase in food prices was close to 10%, and food price inflation has remained elevated since 2019—well before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic or the Ukraine war. This suggests that domestic factors are driving this inflation. Given that food constitutes a substantial portion of the consumer price index (CPI), high food inflation has contributed to an overall higher inflation rate in the country.

The Importance of Food in Household Expenditure

In India, food accounts for nearly 50% of household expenditure—a much higher proportion than in developed countries like the United States, where the share is less than 10%. The high share of food expenditure indicates a lower standard of living and greater vulnerability to rising food prices. Ignoring food price fluctuations in inflation targeting would mean overlooking what matters most to a large portion of India’s population.

Transitory Fluctuations of Food Prices

The rationale for excluding food prices is often based on the assumption that food price fluctuations are ‘transitory’—that increases are inevitably followed by decreases. However, this is not true for India, where food price inflation has not been negative in any of the 13 years since 2011-12, the base year for the current CPI. Thus, the claim that food price spikes are temporary does not hold for India.

Questioning the Economic Survey’s Proposal

The Economic Survey’s proposal to remove food prices from the inflation target raises two key questions.

● First, is this move justified from a policy perspective?

● Second, would the RBI be more successful in controlling core inflation than it has been with headline inflation?

The answer to both questions is likely ‘no.’

Inflation Targeting Policy

Challenges of Inflation Targeting in India and Globally

Since 2016, India has followed a policy of inflation targeting, wherein the RBI is responsible for controlling inflation through variations in the interest rate. This policy creates the impression that the central bank can precisely control the inflation rate. However, this has not been the case. The RBI has missed its 4% inflation target every year for the past five years. This challenge is not unique to India. In the United Kingdom, the Bank of England has also struggled to meet its inflation targets. In the United States, where the Federal Reserve aims for 2% inflation, the rate shot up to over 8% in 2022 before falling closer to the target. In all these economies, fluctuations in global food prices have influenced inflation trends.

The Core of India’s Inflation Problem

At the heart of India’s inflation problem is the rising price of food. Excluding food prices from the official inflation measure will not solve the issue. If food prices continue to rise, as they have for the past five years, the RBI will struggle to control core inflation. The current inflation in India requires supply-side measures that increase agricultural productivity. Although the challenges are significant, they are not insurmountable for a country that ended chronic food shortages over half a century ago. Success will require a comprehensive approach to agricultural production, one that keeps costs in check so that food supply remains steady as the population and economy grow.

Core Inflation Targeting

Ineffectiveness of Targeting Core Inflation in India

The suggestion that the RBI should focus on core inflation is also flawed. Over the past 13 years, annual average core inflation has remained within the target of 4% in only one year, and even then, barely so. This is not surprising, as two key factors undermine the effectiveness of the RBI’s interest rate policy in controlling core inflation.

Impact of Repo Rate on Core Inflation

First, increasing the repo rate does not dampen core inflation as expected. In fact, it may lead to higher inflation. When interest rates rise, firms may increase prices to maintain their profit margins, especially since they face higher working capital costs and reduced revenues due to lower aggregate output.

The Role of Food Price Inflation in Core Inflation

Second, food price inflation is a key determinant of core inflation. This makes sense, as food prices influence wages, which in turn affect the costs of production across the economy. Therefore, food price inflation impacts core inflation, rendering the concept of core inflation targeting meaningless in this context.

Rethinking Inflation Targeting

The Ideological Shift in Economic Policy

Despite the limitations of inflation targeting, why does India persist with this approach? The answer lies in a global ideological shift that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. The prevailing view became that production should be left to the market, while inflation control was the responsibility of central banks. Since 1991, political parties in India have adopted this Western practice, even when it may be irrelevant or damaging to the country’s unique economic context. The suggestion to exclude food prices from the inflation target is one such misguided practice.

The Need for Comprehensive Inflation Control

Removing food inflation from the inflation target without a plan for controlling it would leave India vulnerable to rising food prices, which threaten the standard of living for a large portion of the population. The Economic Survey suggests that income transfers to households could offset the negative welfare effects of food price inflation. However, if food prices continue to rise faster than the overall inflation rate, as they are currently, these transfers will consume an increasing share of the Budget, leaving fewer resources for public goods. This is an undesirable outcome.

Conclusion

There is no alternative to controlling the rise in the prices of all goods, including food. The rising price of food is central to India’s inflation problem, and addressing it requires a comprehensive and sustained focus on agricultural production. Simply excluding food prices from the inflation target is not a viable solution and could have detrimental effects on the country’s economy and welfare.

|

Probable Questions for UPSC Mains

|

Source: The Hindu