Context:

Food inflation in India has taken an interesting turn, diverging from the global trend. While world food prices have experienced a significant decline, India continues to grapple with sticky and elevated inflation. This shift can be attributed to various factors, including global events such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine, domestic production dynamics, and government policies aimed at insulating the Indian economy from external price pressures.

Global Food Price Trends:

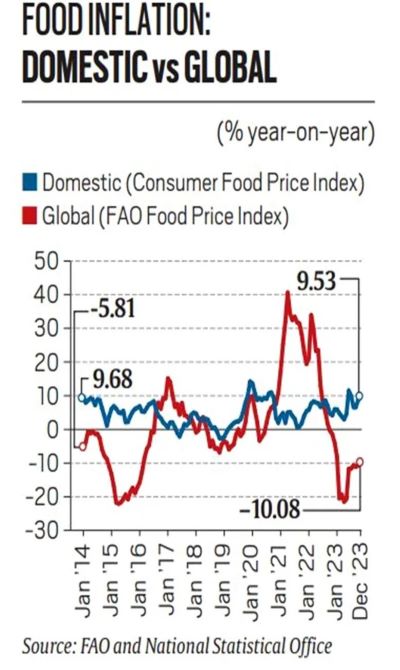

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) food price index, a key indicator of global food prices, witnessed a substantial decrease from its peak in 2022. The index, which reflects a trade-weighted average of world prices for a basket of food commodities, fell by 13.7% in 2023. The contrast with India's official consumer food price index is stark, as domestic inflation remained stubbornly high at 9.5% in December 2023.

Global food inflation, as measured by the FAO index, has been in negative territory since November 2022, while India has grappled with persistently high inflation. This divergence is notable when comparing the volatility of international food price increases to the relatively stable range of domestic inflation in India over the last decade.

Limited Transmission of Global Prices to India:

The limited transmission of international prices to food inflation or deflation in India is a key factor in this divergence. This transmission typically occurs through imports and exports, particularly in commodities where India is significantly import-dependent. For example, disruptions in global supply chains, driven by events like the Russia-Ukraine conflict, led to a surge in domestic retail edible oil inflation in India.

However, the scope for such transmission is mostly limited to commodities like edible oils and pulses, where India relies on imports for over 60% of its annual consumption. In contrast, India is not only self-sufficient but also an exporter in several other food categories, such as cereals, sugar, dairy, poultry, fruits, and vegetables.

De-Globalization of Food Inflation in India:

The Indian government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has taken deliberate steps to de-globalize food inflation. This has been achieved through measures such as imposing restrictions on exports and facilitating imports of major pulses and crude edible oils with minimal duties until March 31, 2025. As a result, the threat of imported inflation has been practically ruled out, even in the face of low global prices for key commodities.

For instance, the ban on exports of wheat, non-basmati white rice, sugar, and onions has closed the potential route for export-led inflation. Despite ongoing challenges in the Red Sea due to attacks by Yemen's Houthi militants, the impact on significant food item imports into India appears to be minimal. Imports of pulses and edible oils, crucial components of India's food basket, remain largely unaffected by disruptions in the Red Sea region.

Global Cues and Impact on Imports:

While challenges in the Red Sea may disrupt vessel movements, especially those following the traditional shipping lanes from the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal, their impact on India's major food imports seems limited. For pulses, which mainly come from Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, and Myanmar, and edible oils from Indonesia, Malaysia, Argentina, and Brazil, alternative routes can be utilized.

Although vessels carrying sunflower oil from Russia and Ukraine face challenges circumnavigating the African continent, sunflower oil constitutes a small share of India's total edible oil imports. The larger volumes of palm oil and soybean, which are critical for India's edible oil market, remain relatively unaffected by the disruptions.

Domestic Factors Driving Food Inflation:

Looking ahead, the trajectory of food inflation in India is likely to be more influenced by domestic factors, particularly in terms of production. Crops such as cereals, pulses, and sugar emerge as key areas of concern, impacting staple food items like wheat, pulses, and sugar.

Retail inflation for cereals and pulses was recorded at 9.9% and 20.7% year-on-year, respectively, in December. Pulses inflation has remained in double digits since June 2023, reflecting sustained pressure on these essential commodities. The government's comfort is derived from the increased area sown under wheat, indicating a potential bumper harvest. However, challenges such as heat stress during the critical grain formation period could pose risks to wheat yields.

In the sugar sector, mills commenced the new season in October 2023 with historically low stocks, and uncertainties prevail regarding actual production by the time crushing concludes in April-May. Furthermore, in the pulses segment, elevated prices are exacerbated by a decrease in the area planted during the current rabi season.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the de-globalization of food inflation in India is a result of a strategic approach by the government to insulate the economy from external shocks. By limiting the transmission of global prices through export restrictions and facilitating imports with minimal duties, India has successfully reduced its vulnerability to international price fluctuations. The current trajectory of food inflation in India is shifting towards being more influenced by domestic factors, particularly production dynamics for key crops. As the nation navigates these challenges, policymakers will need to strike a delicate balance between ensuring domestic food security and managing inflationary pressures.

|

Probable Questions for UPSC Mains Exam

|

Source – Indian Express