As India and China mark 75 years of diplomatic relations in 2025, the milestone is not merely ceremonial. It arrives amid shifting geopolitical currents in Asia and globally. What began in 1950 with mutual recognition and the promise of Asian solidarity has now evolved into a multi-layered relationship defined by unresolved territorial disputes, deep economic interdependence, strategic competition, and selective cooperation. This dynamic, often described as “competitive coexistence”, is the defining paradigm of 21st-century India-China engagement.

Historical Context and Evolution

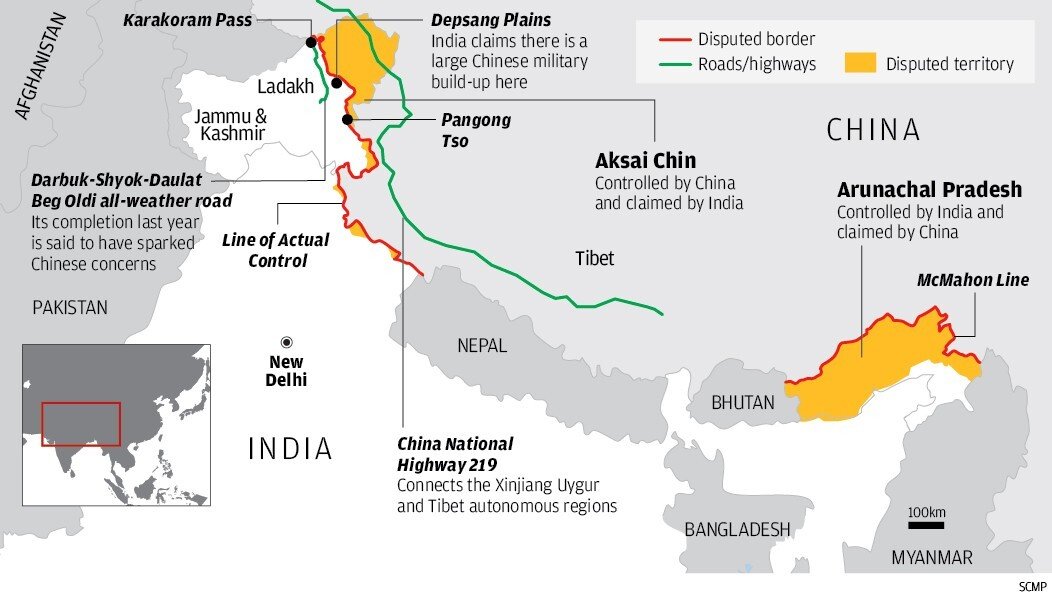

- India was among the first non-communist nations to recognize the People’s Republic of China in 1950, and both countries initially espoused principles of Pan-Asianism and non-alignment. The Panchsheel Agreement of 1954 sought to establish peaceful coexistence. However, the optimism was short-lived. The Sino-Indian War of 1962, triggered by disputes over the Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh (South Tibet in Chinese terminology), ruptured trust and remains a foundational trauma in bilateral ties.

- Tensions have persisted over the Line of Actual Control (LAC)—the de facto border—especially in regions like Eastern Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh. The deadly Galwan Valley clash in 2020, which claimed the lives of 20 Indian and at least four Chinese soldiers, marked a watershed moment, triggering a major doctrinal shift in India’s China policy. Engagement is now conditioned by the realities of military preparedness, sovereign assertiveness, and long-term strategic competition.

The Strategic Centrality of China in Indian Foreign Policy

Today, China is arguably the most influential external variable shaping Indian strategic planning. Every major foreign policy and defence decision—whether infrastructure development in the Himalayas, naval presence in the Indian Ocean, or participation in regional multilateral platforms—is influenced by China’s actions and posture.

- Military Dimension: Over 60,000 Indian troops are now permanently deployed along the Eastern Ladakh sector of the LAC. Both sides have undertaken massive infrastructure upgrades—China via the Western Theater Command and India through strategic roads, bridges, and advanced logistics along the border.

- Border Dispute Status: Despite numerous rounds of corps commander-level talks and diplomatic engagements, the status quo remains precarious. China continues to resist disengagement at key friction points, while India insists on a return to pre-April 2020 positions for normalcy to resume.

Economic Interdependence:

Despite strategic tensions, bilateral trade has remained resilient, reflecting the structural nature of economic interdependence:

- Trade Volume: In FY 2024–25, bilateral trade stood at over $115 billion, with a trade deficit of nearly $100 billion in China’s favour.

- Sectoral Dependencies: India remains heavily dependent on China for:

- Pharmaceuticals: 60–70% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are sourced from China.

- Electronics: Nearly 80% of India’s smartphone components and consumer electronics imports originate from China.

- Solar Panels: China supplies around 80–90% of India’s solar module requirements.

While India has taken steps under the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme to boost domestic manufacturing in key sectors, complete economic decoupling is unfeasible in the near term. Instead, the government is promoting supply-chain diversification and risk mitigation, particularly in strategic sectors.

South Asia as the New Battleground

China’s growing footprint in South Asia poses a direct challenge to India’s traditional sphere of influence:

- Strategic Infrastructure Projects:

- Sri Lanka: Lease of Hambantota Port for 99 years under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

- Nepal: Development of Pokhara International Airport and other BRI-linked infrastructure.

- Maldives: Major investments in housing and connectivity.

- India’s Countermeasures:

- Increased development assistance and capacity-building.

- Emergency response leadership (e.g., earthquake and pandemic relief).

- Enhanced defence cooperation and concessional credit lines.

However, China’s chequebook diplomacy and information influence campaigns have made it essential for India to move beyond episodic, reactive engagement to a more institutionalised, people-centric regional strategy.

The Bangladesh Factor and Geopolitical Spillover

Recent developments with Bangladesh have highlighted the sensitive nature of India’s neighbourhood strategy:

- Controversial Remarks: Interim leader Mohammad Yunus referred to India’s Northeast as “landlocked” while in Beijing—geographically correct but diplomatically provocative.

- Strategic Risk: Bangladesh has allowed Chinese investment near the Lalmonirhat airbase, close to the Siliguri Corridor, a narrow, strategically vital strip that connects India’s mainland with its northeastern states.

- Economic Retaliation: India suspended transhipment support critical for Bangladesh’s Ready-Made Garment (RMG) exports, which contributed US$0.5 billion in 2024, affecting 4,000 factories and over 4 million workers.

This also impacts the BBIN (Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal) Corridor and BIMSTEC Master Plan on Transport Connectivity worth $124 billion, undermining regional trade momentum (which is already low at 5% intra-regional trade, compared to ASEAN’s 25%).

The Water Security Challenge

China’s plans to build a dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) near the Arunachal Pradesh border have raised alarms in India:

- No Water-Sharing Treaty: Unlike with Pakistan (under the Indus Waters Treaty), India and China lack any binding water-sharing framework.

- Risk of Weaponisation: Concerns of unilateral diversion, data opacity, and ecological damage persist.

- Recent Progress: Expert-Level Mechanisms on hydrological data-sharing were resumed in 2025, but trust remains minimal.

Conclusion

The 75th anniversary of India-China diplomatic ties is a moment not for sentiment, but strategic clarity. In an era of geopolitical uncertainty, the bilateral relationship remains a defining element of Asia’s stability—or its volatility. China will continue to challenge India structurally, but it also reflects the need for India to build internal capacity, secure strategic autonomy, and define a long-term vision for regional leadership.

As India steps into this role, it must act not just as a regional balancer but as a custodian of Asian order, investing in institutions, infrastructure, and ideas that can shape the continent’s future. The road ahead lies in managing rivalry without magnifying risk, engaging without conceding, and building guardrails that turn friction into a framework for coexistence.

| Main question: Analyze how China’s increasing presence in South Asia is altering the regional strategic calculus for India. What steps has India taken to maintain its primacy? |