Context

- The 2014 report by Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) underscored the significant role of the energy sector in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, attributing 35 percent of total anthropogenic GHG emissions to this sector.

- Despite initiatives like the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol, emissions from the energy sector increased more rapidly between 2001 and 2010 compared to the previous decade.

- The growth rate of energy sector GHG emissions accelerated from 1.7 percent annually during 1991-2000 to 3.1 percent per year from 2001-2010.

- This surge was primarily driven by rapid economic growth in developing countries, especially China and India, and an increased reliance on coal.

- The report predicted that, without effective mitigation policies, energy-related CO2 emissions could rise to 50-70 GtCO2 by 2050.

- Stabilizing atmospheric CO2 concentrations would require global net CO2 emissions to peak and then decline towards zero, with low-carbon energy sources expanding their share in electricity supply from 30 percent to 80 percent.

Promises

Following the release of the report, China announced in 2014 its intention to peak CO2 emissions around 2030 and to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in its primary energy consumption to around 20 percent by the same year. While India did not make a similar commitment in 2014, expert opinions have suggested that India might achieve peak carbon emissions by 2040-45.

Progress

- As of 2022, China had made significant strides towards its 2030 target, with non-fossil fuels accounting for 18.37 percent of its primary energy mix. India, although without a specific target, derived 11 percent of its primary energy from non-fossil fuels in the same year. Globally, non-fossil fuels made up about 18.2 percent of primary energy in 2022, meaning that over 82 percent still came from fossil fuels. Coal’s share in the global primary energy mix increased by 5 percent from 2003 to 2013, reaching 29 percent, making it the second most important fuel after oil. Projections from 2013-14 anticipated that China would remain the largest coal consumer, accounting for 51 percent of global consumption, with India expected to take the second spot by 2024. This projection materialized earlier than expected.

- Moderate projections expected China's coal demand growth to decelerate significantly, peaking by 2030. Structural changes and policy measures, such as China's shift from a manufacturing-driven economy to one driven by services and domestic demand, along with efficiency improvements and stringent environmental policies, were expected to drive a rapid decline in coal demand. Ambitious projections even predicted that China would stop importing coal by 2015 and that its coal demand would start declining by 2016.

Current Trends

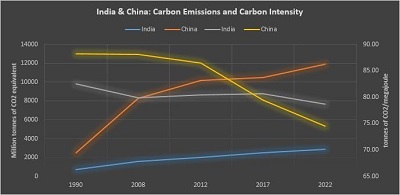

- However, in 2022, China’s coal consumption was 88.41 EJ, accounting for over 54.8 percent of global coal consumption. Although the growth in coal consumption in China had slowed to an annual average of 0.9 percent from 2012-2022, compared to over 9 percent from 2002-2012, it had not peaked as some projections had anticipated. China's GDP grew at an annual average of 10.7 percent from 2002-2012 and at 6.25 percent from 2012-2022. In contrast, India's coal consumption grew at an annual average of over 6.2 percent from 2002-2012 and at 3.9 percent from 2012-2022, while its GDP grew at an annual average of 6.9 percent from 2002-2012 and at 5.6 percent from 2012-2022.

- This sustained economic growth in China and India without a proportional increase in coal consumption indicates a degree of decoupling between carbon emissions and economic growth. The coal intensity of the Chinese economy has fallen by over 48 percent in the last two decades, while India's coal intensity fell by about 18 percent. Services, which are generally less energy-intensive, contribute a larger share to India's economy than China's, but India's lower coal use efficiency results in higher coal intensity.

Structural and Policy Measures

- China committed to reducing the carbon intensity of its economy by 40-45 percent during 2005-2020. However, from 2002-2009, China's carbon intensity increased by 3 percent due to a shift towards a more carbon-intensive economic structure. Accelerating progress towards peak emissions in China could potentially drive industries to less efficient countries, thus increasing global carbon emissions.

- For China and India to reduce emissions and achieve material prosperity, economic growth must be decoupled from energy-related emissions. While theoretically possible, this transformation would impose considerable costs, as highlighted by the Katowice Committee of Experts under the UNFCCC in June 2023. They acknowledged that developing countries would bear a disproportionate cost of decarbonization.

The Role of OECD Countries

The reduction in carbon emissions achieved in OECD countries often occurred without radical policy interventions. Many OECD nations decarbonized by shifting towards less carbon-intensive fuels and through structural changes in their economies, such as a transition to service-oriented systems. Additionally, exporting polluting industries to other countries played a significant role. For instance, Japan had a policy of locating heavily polluting industries abroad, and European countries reduced carbon emissions by exporting production to developing countries while increasing imports of embodied carbon.

Current Emission Trends

As of 2022, global carbon emissions were 64 percent higher than in 1990, the year of the first IPCC report, and 5.2 percent higher than in 2015, the year of the Paris Agreement. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when economic activity slowed dramatically, carbon emissions only fell by about 6 percent in 2020 and rebounded quickly after restrictions were lifted. Current projections suggest that to meet climate targets, the world must reduce CO2 emissions per unit of real GDP by around 9 percent annually, a rate nearly five times greater than historical averages.

Conclusion

The burden of decoupling carbon emissions from economic growth falls heavily on developing countries like China and India. Current methodologies for sharing carbon emission reduction efforts are based on equal marginal abatement costs, which disadvantage emerging economies with lower historical emissions. Achieving significant reductions in carbon intensity requires unprecedented rates of decarbonization. For China to peak emissions by 2030, a 4.5 percent annual reduction is needed, while India would require even more drastic measures. The debate on decarbonization often overlooks the practical challenges faced by developing countries, which prioritize economic growth. Rich countries, facing their own economic pressures, are unlikely to make deep cuts to GDP or provide substantial financial aid. It is crucial for the discourse on decarbonization to address these realities and explore feasible strategies for sustainable development.

|

Probable Questions for UPSC Mains Exam

|

Source – TORF