Caste has long been a defining factor in India's social and political landscape, influencing access to resources and opportunities. While affirmative action policies and constitutional provisions aim to rectify historical caste-based inequalities, the issue of accurate caste data remains a contentious topic. Advocates for a caste census argue it is essential for fair allocation of resources, determining reservations, and addressing caste-based disparities. Accurate data, they claim, would allow for better-targeted welfare programs and more inclusive policy-making.

· However, the idea of conducting a caste census raises significant challenges. Past attempts at caste enumeration have been marred by inaccuracies and biases. The complexities of caste mobility, misclassification, and socio-political dynamics make it difficult to capture reliable data. Thus, while a caste census could potentially promote equity, its execution faces significant hurdles. Understanding these historical, logistical, and social challenges is crucial in assessing whether it can effectively contribute to social justice and inclusion in India.

Historical Context of Caste Censuses in India

The practice of caste enumeration dates back to the colonial era, with the British administration using caste data to structure governance. Over time, caste-based censuses became both tools for administrative convenience and instruments for social stratification.

Key Milestones in Caste Enumeration

1. 1871–72 Census: The first detailed caste census highlighted the arbitrary and inconsistent classification of castes across regions.

2. 1931 Census: This was the last comprehensive caste census conducted in India, identifying 4,147 castes. It revealed inaccuracies, as communities claimed different identities in various regions.

3. Post-Independence Era: The focus shifted to broader socio-economic classifications, and caste enumeration was discontinued in decadal censuses. However, the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) 2011 attempted to collect caste data. It recorded a staggering 46.7 lakh caste categories, with over 8.2 crore acknowledged errors, underscoring the complexity of caste classification.

Challenges in Conducting a Caste Census

Despite its potential benefits, conducting a caste census poses several logistical, methodological, and social challenges.

Caste Mobility and Misclassification

1. Upward Mobility: Many individuals and communities may identify with higher castes to claim perceived social prestige.

2. Downward Mobility: Post-independence, reservation policies have incentivized some groups to claim lower caste status to access affirmative action benefits.

3. Similar-Sounding Castes: Identical or similar surnames across regions (e.g., ‘Dhanak,’ ‘Dhanuk,’ and ‘Dhanka’ in Rajasthan) create confusion and misclassification, complicating data collection.

Enumerator Bias: The sensitive nature of caste inquiries often causes enumerators to rely on assumptions, particularly through surnames, rather than directly asking respondents. This bias risks skewing data and undermines the reliability of findings.

Data Accuracy: Historical records and contemporary surveys, such as Bihar’s 2023 caste census, reveal significant inconsistencies in caste data. For instance, the Bihar Census included over 215 communities but faced challenges in accurately categorizing groups due to caste fluidity and diversity.

Proportional Representation: A Complex Challenge

One of the primary arguments in favor of a caste census is to enable proportional representation in reservations and policy benefits. However, implementing proportional representation across India’s vast and diverse population poses significant challenges.

Reservation Mechanism: Currently, reserved positions in education and employment are distributed proportionally (e.g., every 4th position is reserved for OBCs under the 27% quota).

Impracticality of Representation: India’s population of 1.4 billion includes over 6,000 castes. The average caste size is approximately 2.3 lakh people. Smaller castes, with populations as low as 10,000, would require over 1.4 lakh vacancies to secure a single reserved position, as seen in recruitment processes like the UPSC. This scale of representation is unfeasible, potentially leading to further exclusion of minor castes.

Insights from the Bihar 2023 Caste Census

Bihar’s caste census offers a case study in addressing the challenges and benefits of collecting caste-based data. Conducted in two phases in 2023, the census categorized over 98% of the state’s population into backward classes (BCs), general categories (GCs), most backward classes (MBCs), and scheduled castes (SCs).

Key Findings

1. Income and Education Disparities:

o Over 40% of SC and ST households earn below ₹6,000 per month, compared to 25% of GCs.

o Dalit incomes average ₹8,000 per month, significantly lower than the ₹39,000 average for Kayasthas.

o Higher education attainment among Dalits is less than 3.5%, compared to 17% among GCs.

2. Employment and Asset Ownership:

o Forward castes dominate public and private sector employment, while SCs are largely confined to manual labor.

o Marginalized groups like Musahars and Bhuiyas struggle with kutcha housing and homelessness.

3. Intra-Cluster Disparities:

o Even within clusters like BCs and MBCs, disparities persist. Some MBC groups, such as Dangis and Halwais, perform better socio-economically than many BCs.

Implications of the Findings

The census underscores the need for granular caste data to ensure equitable resource distribution. However, it also highlights the risk of exclusion and misrepresentation of minor castes within broader administrative categories.

The Debate on the Creamy Layer and OBC Representation

The term "creamy layer" was defined by the Supreme Court of India in the 1992 Indra Sawhney case, referring to the more affluent and better-educated sections of OBCs who are excluded from reservation benefits. It was formalized through a government memorandum on September 8, 1993.

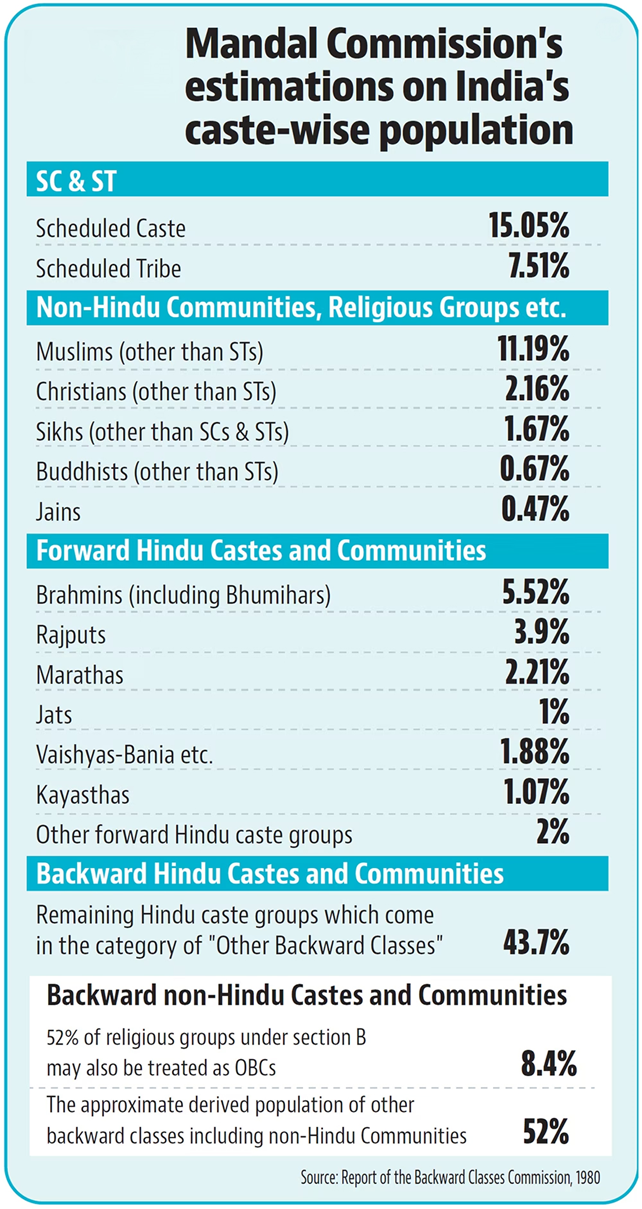

Despite these provisions, data from 2019–2021 shows that OBCs constitute approximately 42% of Indian households, making them the largest socio-economic group. A caste census could provide accurate population data for OBCs, helping policymakers revisit the reservation cap and address intra-group disparities.

Administrative and Policy Implications

· Policy Implementation: While proponents of a caste census argue for its utility in equitable resource allocation, the complexities of caste data risk exacerbating social divisions. A poorly executed census could deepen existing inequalities rather than alleviate them.

· Exclusion of Minor Castes: Minor castes risk being excluded due to disproportionately low representation in broad administrative categories. This exclusion undermines the principle of inclusivity that a caste census seeks to uphold.

· Administrative Burden: Conducting a caste census would require substantial logistical and financial resources, potentially diverting focus from other pressing developmental priorities. For instance, resolving inaccuracies from the SECC 2011 cost significant time and resources, limiting its utility in policy formulation.

Conclusion

While the idea of a caste census is rooted in achieving equity and addressing historical injustices, its execution involves significant challenges. Historical evidence highlights the complexities of caste classification, while contemporary data underscores the risks of exclusion and misrepresentation. Additionally, the logistical and administrative burdens of such an exercise cannot be ignored.

Rather than focusing solely on caste-based enumeration, alternative approaches prioritizing socio-economic indicators and fostering inclusivity could offer more sustainable solutions. Policymakers must balance the need for detailed caste data with the imperative to avoid exacerbating social divisions, ensuring that efforts to promote equity and justice truly benefit the most marginalized communities.

| Main question: Discuss the challenges and implications of conducting a caste-based census in India. How do caste-based reservations and affirmative action policies contribute to social justice in the country? |